In today’s medical vocabulary, words like “empathy,” “communication,” and “patient-centered care” are repeated so often they risk becoming mantras. The repetition feels compensatory, as if naming these values could make up for how little they are actually experienced. For most people navigating the healthcare system, the sense is not of being truly heard, but of moving through a clinical architecture where the patient’s voice is secondary — tolerated within procedural limits, rarely treated as knowledge in its own right.

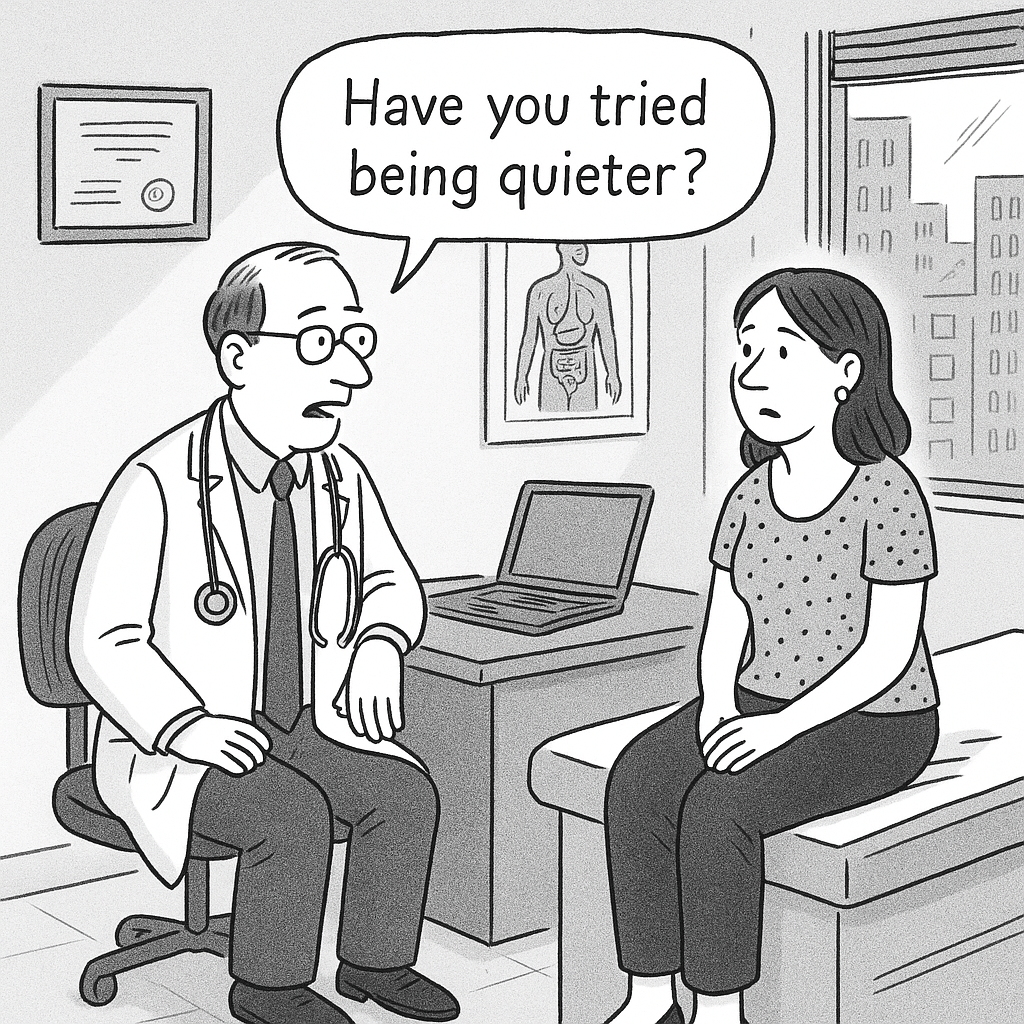

This is not just a minor relational gap that could be fixed with a little extra goodwill. The problem runs deeper. In many medical settings, listening has been systematically excluded from the domain of knowledge. At best, it is seen as a kindness; at worst, as an inefficiency that slows things down. The result is a widespread but rarely acknowledged suffering: the pain of not being heard — what I call Unheardalgia. It shows up in small, almost invisible ways: in the minutes shaved off an appointment, in the averted gaze, in the silence left hanging, in charts where lived experience is flattened into symptoms and symptoms into codes. Unheardalgia is the product of an epistemology that sees the other not as a co-author of knowledge but as noise to be filtered, processed, and fit into pre-existing frameworks.

On this very point, Rachael Bedard’s recent article in The New Yorker offers a striking case study. She follows Yale School of Medicine researchers Harlan Krumholz and Akiko Iwasaki, whose clinical project — aptly called LISTEN — seeks to give patients not only the chance to speak but the right to shape the very questions medicine asks. This is more than a feel-good story. It’s a radical proposal: that clinical knowledge is incomplete unless it is disrupted, refracted, even re-written through the voices of those who live it.

“When I didn’t know my patients — when I knew nothing about them, didn’t look them in the eye — everything was easier,” Krumholz admits. “Now that I have a connection with a whole community, it’s different.” The honesty of this confession is bracing. It reminds us that every act of knowing is partial if it refuses the encounter — and the unsettling vulnerability that encounter entails. The much-celebrated “neutrality” of medicine can become the most sophisticated way of excluding the other.

Listening, then, is never a neutral gesture. It requires suspending judgment, giving up control, making space for the unexpected. That’s precisely why it resists the tempo of performative medicine, which prizes efficiency, predictability, and order. There is no care without listening — and no listening without a willingness, however brief, to disarm oneself in front of the enigma of the person speaking.

Seen in this light, Unheardalgia is not a minor frustration but an ontological wound: the failure to be recognized as a speaking subject. It is a pain that precedes treatment and often survives it. The cruel paradox is that, in the very place where we should feel most fully seen, we can feel most fragmented and invisible. The chart holds everything except what matters most: the need to be regarded as someone, not just something.

Of course, medicine operates under pressures that demand standardization — evidence-based protocols, validated classifications, uniform treatments. And yes, systemic barriers to authentic listening are real: the relentless time pressure of clinical schedules, the legal climate that favors defensive documentation, the administrative overload, the fragmentation of care. These constraints must be acknowledged, but not allowed to become permanent excuses.

The question is whether simply naming the problem is enough — or whether it should be the starting point for a deeper transformation. What is needed is not just structural reform or the goodwill of individual clinicians, but a radical rethinking of medical education itself. Only by reshaping how we train future physicians can we restore care to its relational core.

This is not about “humanizing medicine,” a phrase that sounds comforting but does little conceptual work. It’s about interrogating the regime of truth that governs medicine — a regime that equates evidence with reality and risks mistaking what is measurable for what is meaningful. Ethical communication should be treated not as a soft skill but as a foundational discipline, one that reframes the clinical encounter as a shared act of knowing.

Communication ethics is not simply good manners or polished bedside talk. It is a critical practice, demanding reflection on what it means to meet another person in vulnerability, and on the weight carried by every word spoken or withheld. It is here that another way of knowing becomes possible — one where precision does not exclude resonance, and truth is measured not only in data but in the quality of attention.

Medicine that does not listen is not just inadequate — it is epistemologically blind. And unless clinical culture can confront this blindness, it will continue to fail precisely where it believes itself most effective. No diagnostic machine, however sophisticated, can restore the meaning of being ill. No therapy can truly transform unless it is born from the recognition that the patient is not merely a recipient of care but a co-author of it.